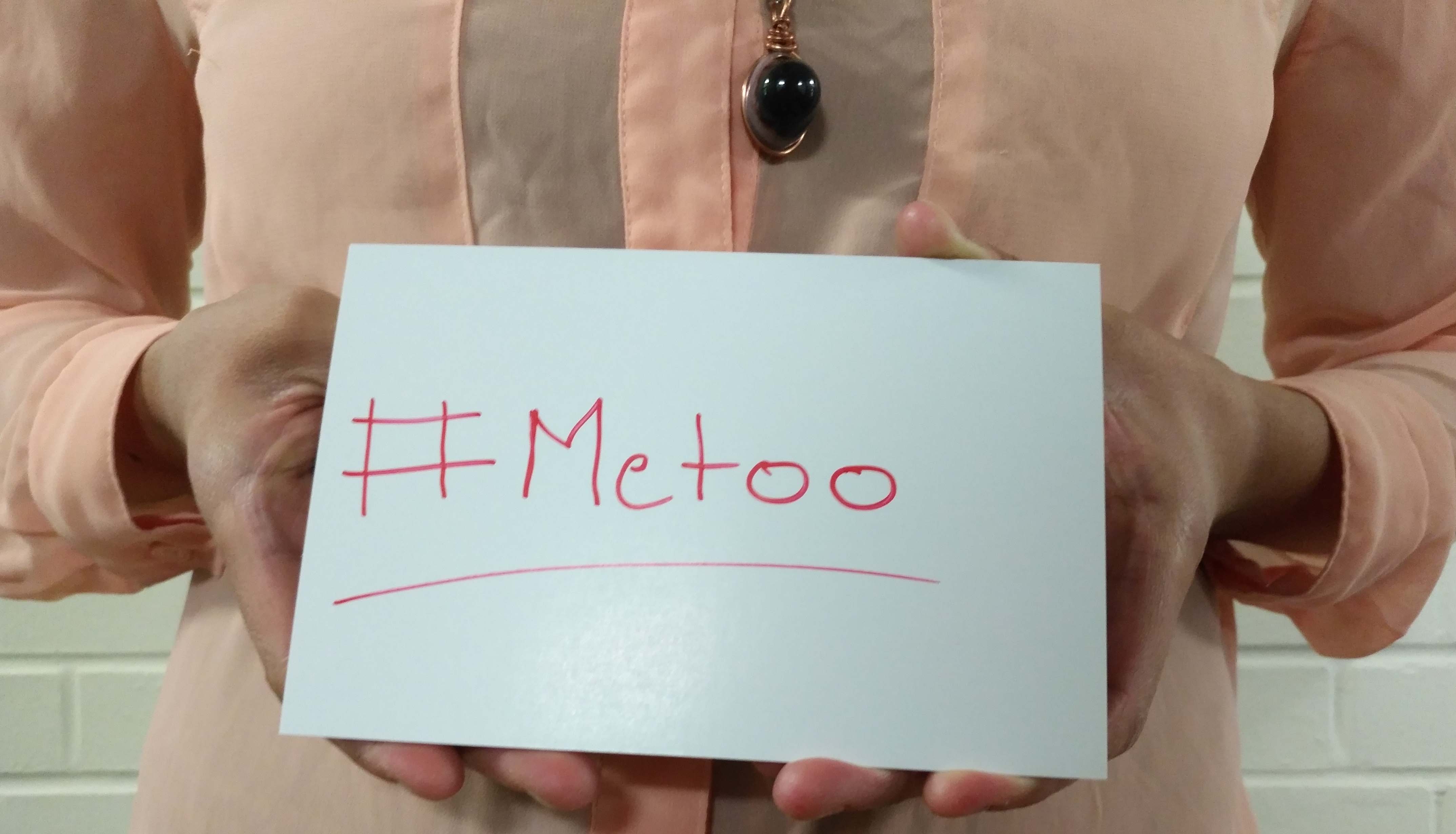

The #metoo campaign, originally created by activist Tarana Burke in 2007, picked up steam this week when Alyssa Milano urged women to use the hashtag in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein accusations that have rocked Hollywood. The campaign has always been meant to unite survivors of sexual harassment and sexual assault, providing them with a platform to share their experiences or simply stand in solidarity with the sea of women who have had to deal with these things in their lives—arguably every woman in the world.

But as social media was flooded with me toos and harrowing stories of abuse and survival, the campaign was met with a mixed reception. While many applauded it for exposing how prevalent an issue sexual violence is, others lamented the fact that women have been talking about this forever and yet it takes a social media campaign of this magnitude for them to be believed. And while many saw the viral posts as having the potential to cause men to examine their own behaviour and microagressions, others wondered, why is the onus once again on the victims to do that emotional labour? Where are the men holding their friends, their brothers, their kids accountable for their bad behaviour towards women?

Interval House stands by the #metoo campaign and encourages survivors to engage with outlets and communities that assist in their healing. We see the power of solidarity and group empathy every day in our women’s groups. But we can see why this campaign may feel like another example of how society burdens women with the responsibility for their own general safety when what is really needed is for everyone, especially men, to stand up to misogyny and dismantle rape culture.

At Interval House, we believe survivors. We know that when a survivor comes forward, she is telling the truth and we do not think a woman owes anyone her story in order to be believed. But out in the world, when a woman is sexually assaulted, we still see her questioned and scrutinized far more than her attacker. What was she wearing? Was she alone? Why was she there? Was she drinking? Was she flirting? Was she known to be promiscuous?

What we don’t hear are the questions about the accused—questions we can surmise the answers to. Has he done this before? How many times? Did his friends encourage him? Why didn’t he take no for an answer? Would he do it again?

Victim blaming is so par for the course that we still see it in mainstream news stories about violence against women and it is even ingrained in the legal process victims must go through for a shot at justice. That is, if they decide to take legal action at all (and we know that for myriad reasons, many don’t). Newspapers are quick to throw women like Italian actress and director Asia Argento (and Harvey Weinstein accuser) under the bus for not being perfect angels—insinuating, of course, that they were “asking for it”. The media also perpetuates common, harmful misconceptions such as the notion that a woman can’t claim rape if she’s had consensual relations (sexual or otherwise) with the attacker prior to or after an assault. In case there’s any confusion at this point, it’s important to stress that someone’s consent must be given each time an act involving them takes place. Rape can most certainly occur within the context of an otherwise consensual relationship such as friendship or marriage.

Meanwhile, news outlets scramble to find redeeming qualities about accused abusers and rapists. Remember convicted rapist Brock Turner, who the media preferred to see as a star swimmer? How about Dr. Mohammed Shamji? He abused his wife and fellow doctor Elana Fric-Shamji for years before killing her in 2016 but the headlines preferred the title neurosurgeon to accused murderer.

Yes, men are backed up and excuses are made for them when they commit gender-based crimes and women are told to adjust to misogynistic rape culture or risk being the next victim. When we should be seeing zero tolerance for jokes about rape and violence against women as well as tougher sentences for sexual assailants and serial abusers, what we are seeing instead is women being told to dress modestly and consider investing in the emerging rape prevention products on the market today—many of which are designed by men.

Just take a look at this anti-rape underwear line that garnered huge support on their Indiegogo campaign. “We wanted to provide a product that would make women and girls feel safer when out on a first date or a night of clubbing, taking an evening run, travelling in another country, or in any other potentially risky situations,” a spokesperson for the line says in a promotional video. The fact that women have to see any of these run-of-the-mill situations as potentially risky is a huge problem and it’s not one that a modern chastity belt will solve. You know what would make women feel safer out in the world, simply existing? Knowing that men convicted of sex crimes and aggravated assaults against women were given serious sentences, not just slaps on the wrists, and being able to trust that men on the street would not approach them with unsolicited cat-calling and advances.

Undercover Colours made a big splash in 2014 with their nail polish that can detect traces of common date rape drugs. Developed by four men who were engineering students at the time, the nail polish changes colour if a painted finger is dipped in a tainted drink. The men tout the product as part of the solution to campus sexual assault—something experienced by one in six women, according to their website. They do go on to acknowledge that ending sexual assault altogether is the only real solution but it’s a tough pill to swallow that before we could ever see a day when sexual assault and harassment became as socially unacceptable as other violent crimes, we had to see one when rape-prevention products became a blue ocean market, targeting the pocketbooks of women, who already have lower financial security than their male counterparts. And believe me, it is a market. These are just two examples from a plethora of apps, garments, and devices sold to women to prevent their own assaults.

So, the #metoo campaign is great for fostering solidarity and community among women who have been victimized. And it’s good to see that women aren’t as isolated as they once were because sexual assault and intimate partner violence were (and continue to be) seen as taboo topics. But the campaign won’t effect change amongst men, who have long known but easily ignored the fact that women fear for their lives every day, each time they leave the house. And we want to acknowledge here that the fear can be even more pronounced for gender non-conforming folks.

What is needed is for men to stand up, start their own campaign, own up to past wrongs and pledge to do better. What is needed is for men to unravel the toxic masculinity and patriarchal entitlement that tells them they have a right to women’s bodies. What is needed is for men to call each other out when they contribute to sexist dialogue and behaviour. What is needed is for education about consent and respect towards people of all genders to start at a young age so that boys grow up understanding that being a decent human being means extending courtesy and kindness to everyone. What is needed is for the legal system to punish offenders harshly for trespassing on women’s bodies and minds, like they are property to be claimed! And those are just a few examples of how men could help mitigate violence against women.

Holding women responsible for their own protection fails to address the systemic disease of misogyny and rape culture that is hurting all of us. Because without justice, there can be no peace and we have a long way to go before women are afforded the justice they deserve.